Author: HEKS-EPER Uganda

Photo credits: HEKS-EPER Uganda

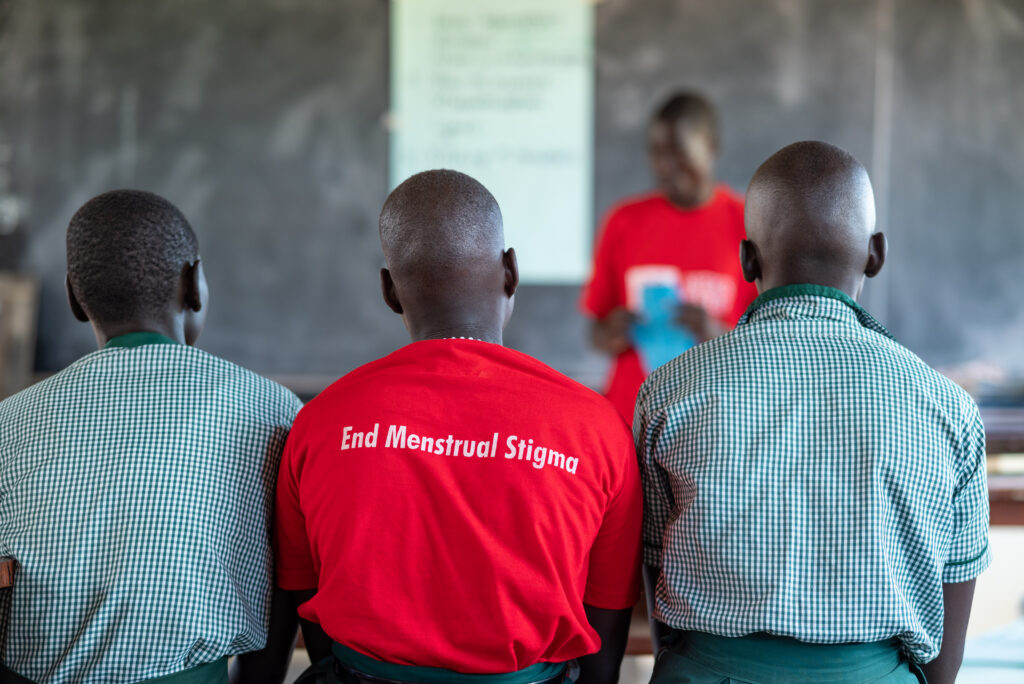

Links to videos: Breaking the silence on MHH, Keeping Girls in School and Menstrual Hygiene Through a Boys Lens

Empowering schools and communities in refugee settlements for effective menstrual hygiene and health

Between 2017 and 2019, Yumbe District recorded a 43% drop-out rate for primary six and seven school girls. The district’s rapid assessment revealed that the lack of menstrual hygiene materials was a major cause of school drop-outs.

HEKS-EPER, supported by the Swiss Water and Sanitation Consortium (SWSC), applies the Blue Schools approach in Yumbe District in West Nile, Uganda, to link Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) in schools with environmental education. Menstrual hygiene management is a key component of the Blue Schools concept.

In Uganda, schools were closed for 22 months during the COVID-19 pandemic, from March 2020 until January 2022. The project team, therefore, conducted sanitation and hygiene campaigns within the community. During this period, the organization noticed that girls were missing meetings in these campaigns and that this was largely attributable to lacking menstrual products to aid their freedom of movement and interaction. It was thus important to respond to this critical need. This was addressed by the prioritization of menstrual health and hygiene by all schools.

HEKS-EPER conducted a school assessment exercise upon the full re-opening of schools in 2022 to find out what would be most urgent in the last year of the project. Learners and teachers chose menstrual hygiene management as a priority for the WASH interventions at their schools. “Menstrual hygiene is important to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals –for example, ensuring healthy lives for all (SDG 3), inclusive, equitable education for all (SDG 4), gender equality and empowerment (SDG 5), and access to safe water and sanitation (SDG 6) -it was important for us to get involved”, says Deborah Nabukeera, Programme Officer, HEKS-EPER.

The exercise was followed by a review of the menstrual health and hygiene landscape with a focus on the Bidibidi refugee settlement (224,000 refugees-UNHCR 2022). This revealed that 73% of menstruating young adults in schools lack access to sanitary pads and adequate infrastructure for bathing, which causes young adults to miss up to three days of school every month.

In this community, menstruation was a silent thing that should not be talked about within the community. When you are menstruating, you cannot even approach anyone for help; at home you are not allowed to touch any dishes or even to cook. You are supposed to leave and sit far away from everyone until you are done with your menstruation.

Agnes Taji, a learner at Knowledge Land Primary School

“We observed three constraints to effective menstrual hygiene management in schools and the community –affordability, stigma, and limited access to water to keep clean”, says Nabukeera. “For example, the available sanitary products were not affordable at USD 1.14, for a packet of 8 pieces, where 88% of families in Uganda earn less than a dollar per day. In refugee communities where work is scarce, there is even less income for an entire family”, observes Nabukeera. “I remember a teacher recounted a scenario of a girl who started menstruating in class, and she sat all day without moving, bleeding on her chair. She had no one to talk to, and she was scared of getting up. For me, this showed the urgency of the situation.”

In West Nile, as in many societies, menstruation is regarded as a shameful secret that should be discussed quietly among women. This, in part, contributes to stigma, disinformation, and negative practices like isolating girls and women who are menstruating. It also limits initiatives to improve access to affordable menstrual hygiene products and supporting facilities like water supply. Although some non-profits intermittently provide sanitary pads in refugee settlements, a lack of funds often affects distribution. Schools lack emergency supplies for girls who start menstruating, and when a girl is sent home, she suffers the trauma of discrimination, bullying, and being laughed at while walking out of class. Consequently, girls of menstruating age choose to leave school or miss school days, affecting their learning. Back at home, menstruating girls are asked to clean themselves with leaves or pour sand and sit on it.

Inclusive interventions for accessible and sustainable menstrual hygiene management

The Blue Schools approach is a multi-sectoral concept developed by the Swiss Water and Sanitation Consortium and implemented by the local partner ACORD (Agency for Cooperation and Research in Development) Uganda to create more awareness on menstrual health and hygiene in schools. “We used a unique, inclusive approach to address cultural taboos and social norms to establish good menstrual hygiene practices that would be accessible to the girls and owned and embraced by the community. We involved all stakeholders, starting from the learners and teachers, the district leadership and UNHCR, which is responsible for refugee issues; we talked with school management committees, we had sessions with girls and boys, and parent-teacher associations, all of which guided us on key issues and messages for menstrual hygiene. Together, we designed training modules to give information about menstruation to help break the stigma within the school and the community”, says Nabukeera.

The project supported seven schools. In total, the schools had more than 5,000 learners without access to sanitary pads implying that girls in these schools spent 27% of the school year at home or in school without actively participating, which affected their learning outcomes. Given the resource constraints in refugee settings, it was important for the project to use locally available resources, both materials and human resources.

Pad-making and menstruation sensitization workshops were organized in schools to give selected learners and teachers accurate information about menstruation and skills to make reusable sanitary pads.

"We focused on child-centered campaigns by engaging the learners in dramas, debates, and competitive games with key messages on menstruation. We fostered teacher-learner, parent-teacher cooperation by building the skills of teachers, learners, and parents in re-useable pad making and good menstrual hygiene practices. The teachers and learners, in turn, delivered these skills and knowledge to other learners during school health club meetings, and health parades”, explains Nabukeera.

Building capacity for more dignity

Moses Otim, the Deputy Head Teacher, discusses the changes arising from the sensitization sessions. “The learners became the change agents by talking about their situation to their parents. Learners also invited community members to debates and football and netball games, where they would talk about menstrual health to help break the stigma. The project even identified Blue Schools Champions from the community and worked with hygiene promoters to conduct community drives at places of worship and water wells.”

By breaking the silence around this taboo, learners and communities were more engaged in the next step around pad-making. “We provided access to what we called ‘dignified menstrual hygiene management’”, says Nabukeera. “We introduced pad-making workshops and selected teachers, learners, school heads, and parents for training. The schools gave us a room and bought the required materials to make reusable pads – manila, scissors, and cloth. Learners were taught during health club meetings, science slots within the Uganda Schools Curriculum as well as break time and weekends to ensure learning and inclusive participation.”

Before this project we used to laugh at girls who were menstruating which made them drop out of school. We did not take care of them; but right now, we know what to do for them. This is a normal body change not a disease. I go to the senior woman teacher to get a pad and give them. I also help provide them with water to wash their pads.

Osuku Henry, a learner at Nyoko Primary School

Like the users, Otim is surprised by the affordability of the re-useable menstrual products they are now making: “Initially, we thought only factories knew how to make pads. The reusable sanitary pad is just like the usual pad bought from the market, but the difference is that this one is made locally. This local pad is much better because you can use it for six to nine months, but the factory one costs four times more and is disposed of after one use.” Parental involvement was, therefore, key to ensuring learners had access to pad-making materials and could continue to do this sustainably at home using old cloths.

My family came from South Sudan fleeing the war and violence in 2017. I have two sisters but I was not allowed to speak about menstruation. If I told my mother that I saw blood on their clothes, she would scold me and forbid me from speaking about it. Now, I know it is not wrong to speak about menstruation, even though I'm a boy. I have also acquired skills in making pads. When my sister starts menstruating, I now know how to help her. Right now, she is able to make for herself a pad I trained her.

Mikaya Lometa, a learner at Knowledge Land Primary School

Keeping more girls in school

Now that more girls in refugee settlements are empowered to make menstrual hygiene products and no longer face discrimination and stigma, schools are filling up quickly and retaining girls. Margaret Amaniyo, Head Teacher at Nyoko Primary School says: “There were only 491 learners when the project started in Nyoko Primary School. Today the school has over 1,063 learners, more than 50% are girls, and has grown to include a boarding facility.” The schools have also introduced emergency clothing and spare uniforms to help girls who start menstruating at school to address the stigma associated with menstruation. Feru Juliet Anguanii, the Senior Woman Teacher, observes: “The girls have a higher enrolment than the boys, and also these days at least 70% of the girls complete primary 7 and cases of girls leaving school have reduced.”

In sustaining the good change in schools, the project relied on the Blue Schools kit and the SWSC learning journey on MHM to support school health clubs to continue the improved menstrual hygiene practices and to be able to train neighboring schools that may be interested in improving menstrual health and hygiene among learners. To support proper menstrual hygiene, piped water was extended and rainwater harvesting tanks (7500ltrs) were installed in schools. This has enabled girls to bathe and manage their menses with dignity. The School Management Committee of Nyoko Primary School purchased pipes to connect the rainwater harvesting tank to the UNHCR reserve water tank to ensure that learners and the community access water throughout the year.

When girls do not have pads, they will just drop out of school because they are scared. I encourage girls who have started menstruating not to fear; I tell them that this is normal and that it also happens to our elders. I teach them how to manage it, and when I have materials, I also make two to three pads for those who do not have them. I encourage them to tell their parents that they are menstruating so that their parents will give them the materials for managing when they are in menstruation so that they can stay in school.

Josephine Kiden, a learner at Knowledge Land Primary School

Ensuring menstrual health and hygiene become national priorities

To consolidate the learnings from this intervention, an advocacy component supported by the Swiss Water and Sanitation Consortium’s Global Advocacy Fund was developed to share information and advocate for menstrual health and hygiene improvements in schools. HEKS-EPER’s menstrual hygiene model has been transformed into a livelihood project with the goal of promoting access to reusable sanitary pads whilst putting income into the hands of communities making reusable sanitary pads, through partnerships with the private sector and community-based organizations.

Menstrual management can be taught to boys so that they know that menstruation is normal. At times at home when you're menstruating and assuming you have brothers and you ask them to help you with anything like pads, they won't help you; they won’t give you money to go and buy menstrual health products so you end up suffering and end up in early marriages, but if they knew that it was normal, they would help you and you would not go for early marriage.

Drileba Sharon, a learner at Nyoko Primary School

What next?

In collaboration with Yumbe District Local Government, CSOs and UNHCR, a menstrual hygiene and health technical working group has been set up at Yumbe District with various implementing partners and civil society organizations to continue taking actions and advocating for menstrual hygiene resources in schools. This will go a long way toward keeping girls in schools, especially in refugee settlements where vulnerability levels are high.

The schools are waiting for no one; they are already trendsetters as model centers for menstrual hygiene management. Knowledge Land Primary School is fundraising to establish a Menstrual Hygiene Management Fund to support the school health club with a sewing machine and reusable sanitary pad-making materials to sell to the community. Ariwa Primary School has partnered with the health centres to support outreach within the community on menstrual hygiene. The health teacher of the school notes that from the capitation grant provided, Ariwa school management has set aside UGX 100,000 per term (USD 27) to support a pad-making fund. The fund is used for purchasing raw materials for making reusable pads.

As the four schools lead in menstrual health and hygiene activities, more schools are inviting them to share their experiences and learning, thus building momentum for good menstrual health and hygiene which is keeping more girls in school.

We will continue to break the silence! remains a resounding commitment in schools.