Authors: Prakash Bohara, Health & WASH Programme Manager, Terre des hommes Nepal; Sudarshan Neupane, Head of Country Office, Terre des hommes Nepal

Contributors : This study was commissioned under the technical guidance from Laxman Kharel, Terre des hommes' Regional Advisor for WASH, and valuable support from Nabin Rana, WASH Project Manager, as well as our partner Geruwa.

Background

Globally, safe management of healthcare waste is a big concern, especially in developing countries. The latest available data (from 2019) indicates that 1 in 3 Health Care Facilities (HCF) globally does not manage healthcare waste safely (WHO 2022). COVID-19 has contributed to a massive increase in healthcare waste, straining already under-resourced HCFs and exacerbating environmental impacts from solid waste.

In Nepal, waste from HCFs has become a matter of major public health concern as most of it is fed into municipal waste management systems, is dumped, burnt in open pits, or incinerated improperly at the site of the HCFs. There are very limited studies that provide an opportunity for local authorities to choose appropriate waste management technologies for primary HCFs.

In this context, Terre des hommes (Tdh) under its WASH in HCF project co-financed through the Swiss Water and Sanitation Consortium conducted a study with the objective to explore methodologies for the characterization and quantification of HCF waste. The study was carried out from 23 to 31 May 2021 in three HCFs in Bardiya district of Nepal – Khairapur, Mohammadpur, and Khairichandanpur. These are rural HCFs with delivery rooms and outpatient consultation services.

Methodology

In this study, the medical waste wascategorised in line with WHO’s Healthcare Waste Management Rapid Assessment Tool (RAT) and its 2011 updates. The categories are the following: (1) infectious waste, (2) sharps waste, (3) Medicinal/ Pharmaceutical waste, (4) Anatomic waste, (5) Radioactive waste, (6) Chemical waste, (7) Other medical waste. General waste was categorised into: biodegradable and non-biodegradable.

Waste collection and weighing were done as follows:Wastes produced from (i) delivery room, (ii) outpatient service, and the (iii) HCF staff were collected separately in plastic bags and then segregated as per the above classifications. Waste generated within 24 hours was transferred for digital weighing and a new plastic bag was replaced at the point of collection to collect the waste for the next 24 hours. This was continued for seven consecutive days. The number of people that produced the waste each day was also recorded. During the study period, the HCFs helped with 6 deliveries, provided consultation to 256 outpatients and had 7 residential staff members.

Key Findings

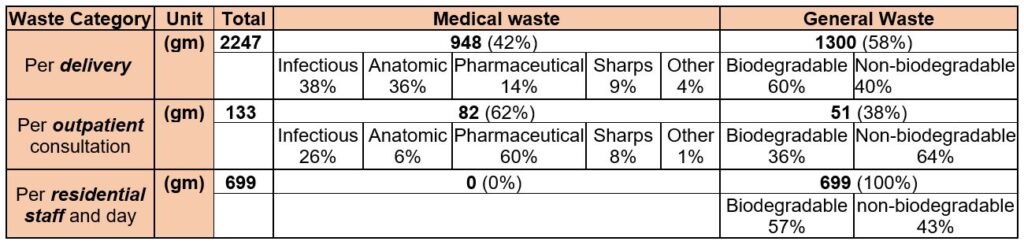

The type of waste and their quantities were found to be as follows:

Comments:

- Regarding personal protection equipment (PPE) in the HCFs used by facility staff and cleaners: apron, gown, and utility gloves are reusable and thus used after reprocessing; surgical gloves and masks are disposed and included here under infectious waste.

- Radioactive wastes are not generated in these HCFs

- Chemical waste, though not generated during the study period, can be produced in the three HCFs e.g. in the labs. However, the labs were closed during the time of the study because of COVID-19 induced lockdown.

The whole process of collecting, segregating, weighing, and recording the wastes generated was conducted by the support staff under the guidance of the Health Facility in-charge. This procedure is simple, cost-effective, and relevant as the team had time and easy access to the HCFs to conduct the study. Remote support from the project staff due to COVID-related travel restrictions was not always very effective compared to communicating with health facility staff on the ground.

Discussion and Recommendations

The categorization of medical waste into seven types – infectious, sharps, medicinal / pharmaceutical, anatomic, radioactive, chemical, and other wastes – and their definition used is based on the WHO (2001/2011) and are found to be relevant by the HCF personnel.

Each waste category can be further categorised by its constituents, which could be taken up in a more in-depth future study of this kind, by segregating and weighing separately the constituents. For example, it is a practice to segregate general waste into the following categories: food, inert (soil, sand, etc), plastics (non-saleable), plastics (saleable), paper, wood-and-leaves, glass, metal, textile, and miscellaneous.

Data on the quantity of waste types generated at a HCF are rarely collected, which makes planning for waste management more difficult. Even though the data collection requires time, the tracking efforts allow facilities to identify where waste separation could be improved and to plan practically how to achieve this. As a result, the amount of waste that needs treatment will be reduced significantly which also reduces costs for safe disposal. In other words, treatment becomes more affordable.

Future Aspirations

Having tested the methodology, the future intension of Terre des hommes is to conduct a more in-depth and scaled-up version of this study, whereby a larger number of HCFs would be targeted which would provide a larger volume of waste to have more representative outcomes. Further general waste would be segregated into ‘recyclable’ and ‘non-recyclable’ in addition to biodegradable and non-biodegradable. To inform programming decisions concerning waste management at national and local levels, as well as to inspire adaptation and piloting of similar methodologies in other countries, Tdh will share a guidance note and tools for waste data collection with the Nepali Government and national and global partners at the end of the project.